It's quite an interesting memoir about Renoir's life and how became and artist and met up with his fellow Impressionists. He's one of the most prolific of the group, with at least 4000 paintings to his record (and the book includes stories about other paintings that were lost or stolen which just made me aghast. Some were literally used to patch up holes in a leaky roof).

“You can never get a cup of tea large enough or a book long enough to suit me.” ― C.S. Lewis

Owned and Unread Project

Wednesday, July 20, 2022

Paris In July: Renoir, My Father by Jean Renoir

It's quite an interesting memoir about Renoir's life and how became and artist and met up with his fellow Impressionists. He's one of the most prolific of the group, with at least 4000 paintings to his record (and the book includes stories about other paintings that were lost or stolen which just made me aghast. Some were literally used to patch up holes in a leaky roof).

Tuesday, June 28, 2022

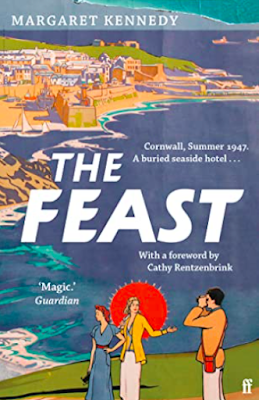

The Feast by Margaret Kennedy

|

| Cover of a 1969 reprint. This one is pretty much perfect. |

|

| The copy of my edition. Nice, but I don't think it really reflects the setting of the book. |

The book then jumps back seven days and describes the final week of the resort and its inhabitants. Set in 1947, the Siddal family are struggling to make ends meet in their ancestral home on the Cornish coast and have converted it to a boarding house, not so much a hotel. Mrs. Siddal is trying to make a go of it but her husband has mentally checked out and doesn't lift a finger, hiding in a room under the stairs. Her three grown sons help but are ready to leave the nest. There are also some servants including Miss Ellis, a snobbish, gossipy housekeeper and Nancibel, the loyal housemaid. Then there are the guests, including two families, the wealthy Gifford family with four children; the Coves, with three; an unhappy couple, the Paleys, who are grieving for their dead daughter; plus an obnoxious clergyman, his put-upon daughter Evangeline; and a late arrival, a bestselling author and her chauffeur. It's almost like an Agatha Christie novel, but instead of a murder, it's a natural disaster, and the reader has to work out who will live and who will die.

|

| The original 1949 cover. Good, but I like the 1969 cover better. |

|

| A French edition from 1956 |

|

| A new French reprint. Good, but a little too cheerful for what's inside the book. |

This is an absolutely brilliant book and I know it will be one of my top reads of the summer, if not the entire year. I've only read one other book by Margaret Kennedy, Troy Chimneys, which is also good but very different from this one. Several of her other books are still in print including her other most famous book, The Constant Nymph, which I also own and will definitely move up on the to-read pile.

I'm counting this as my Classic Set In A Place You'd Like To Visit for the Back to the Classics Challenge. It's also the first read for my Big Book Summer Reading Challenge.

Wednesday, June 1, 2022

Big Book Summer Reading Challenge 2022

- They Were Counted by Miklos Banffy (624 pp)

- The Deepening Stream by Dorothy Canfield Fisher (616 pp)

- Night Falls on the City by Sarah Gainham (632 pp)

- Long Live Great Bardfield by Tirzah Garwood (495 pp)

- My American by Stella Gibbons (480 pp)

- A London Family by Molly Hughes (600 pp)

- The Feast by Margaret Kennedy (448 pp)

- Renoir, My Father by Jean Renoir (456 pp)

- The Gods Arrive by Edith Wharton (454 pp)

- The Most of P. G. Wodehouse (701 pp)

Friday, July 9, 2021

We, the Drowned by Carsten Jensen

I've settled in nicely for Big Book Summer, and at one point last in June I was simultaneously reading THREE giant books between 600 and 900 pages long -- not the best strategy for finishing them in a timely manner. As per usual, one of them really grabbed me and the others were neglected. I plowed through We, the Drowned by Carsten Jensen, finishing it in only five days.

Originally published in Danish, it's the fictionalized story of several generations of a fishing town in southern Denmark called Marstal, spanning just about 100 years. The story begins in 1848 when several of the local sailors are enlisted in the navy to fight the German rebels who have decided they don't want to live under Danish rule any more. Though they bring fully armed ships to blast the German port, they're utterly routed and Laurids Masden, one of the Danes from Marstal, is literally blown into the sky. Miraculously, he survives and becomes a local celebrity, until the fame (among other issues) is too much for him, and he promptly takes to the seas and essentially disappears.

When his son Albert is old enough, he also becomes a sailor, and spends years searching for his long-lost father, spanning the globe. Eventually he returns to Marsden, but is plagued by terrible visions of friends and neighbors embroiled in war.

War was like sailing. You could learn about clouds, wind direction, and currents, but the sea remained forever unpredictable. All you could do was adapt to it and try to return home alive.

Thursday, June 3, 2021

Big Book Summer Challenge 2021

Long Live Great Bardfield by Tirzah Garwood (495 pp)

Trollope by Victoria Glendinning (551 pp)

Slipstream: A Memoir by Elizabeth Jane Howard (528 pp)

A London Family, 1870-1900 by Molly Hughes (600 pp)

Edith Wharton by Hermione Lee (869 pp)

Decca: The Letters of Jessica Mitford (744 pp)

Charles Dickens by Michael Slater (696 pp)

We Were Counted by Miklos Banffy (596 pp)

Painting the Darkness by Robert Goddard (608 pp)

Bella Poldark by Winston Graham (688 pp)

Penmarric by Susan Howatch (735 pp)

Marcella by Mrs. Humphrey Ward (560 pp)

Short Story Collections: (7)

The Portable Dorothy Parker (626 pp)

The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter (495 pp)

The Complete Stories of Evelyn Waugh (640 pp)

The Collected Stories of Edith Wharton (640 pp)

The Most of P. G. Wodehouse (701 pp)

Monday, September 14, 2020

Big Book Summer Wrap-Up

Summer is officially over, and so is the Big Book Summer Challenge hosted by Suzan at Book By Book. I'm very pleased because I finished ten very long books this summer! Eight were from my original list, and two were e-books that I'd been wanting to read. Here's what I read:

Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman (592 pp)

Roughing It by Mark Twain (592 pp)

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson (622 pp)

Fiction:(5)

Imperial Palace by Arnold Bennett (769 pp)

The Twisted Sword by Winston Graham (646 pp)

Temptation by Janos Szekeley (685 pp)

John Caldigate by Anthony Trollope (656 pp)

The Fruit of the Tree by Edith Wharton (652 pp)

Short Stories: (1)

East and West: The Collected Stories of W. Somerset Maugham, Vol. I (955 pp)

Monday, September 7, 2020

Roughing It by Mark Twain: Tall Tales (and Some Racism) in the American West

Saturday, September 5, 2020

Imperial Palace by Arnold Bennett: Upstairs and Downstairs in a London Hotel

|

| The lobby of the famous Savoy Hotel in London, inspiration for the Imperial Palace. It is so posh I was afraid to go inside. |

Saturday, August 8, 2020

The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvilli

|

| Great cover on this Turkish edition |

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

Paris in July: Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette

So, naturally, I had to order Colette's biography Secrets of the Flesh as soon as I returned home. I didn't get around to it at the time, but it's a perfect summer read, for Paris in July and also the Big Book Summer Challenge. I'm always interested in the lives of writers, but I had no idea how scandalous and groundbreaking her life was. Considered the greatest woman writer of France, she wrote 30 books, plus plays, essays, screenplays, and published hundreds of articles and reviews as a journalist. She acted on stage and was notorious for her affairs with both men and women, and married three times.

If you haven't seen the film, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (1873-1954) married the writer/publisher Henry Gauthier-Villars (known as Willy), 14 years her senior, when she was just 20. Willy published a lot of books written by ghostwriters, and when the couple was in need of cash, he took Colette's notebooks, loosely based on her childhood, and published the first story (under his own name) as Claudine at School, the story of a spunky and scandalous girl growing up in a country town. It became an instant success, and three more Claudine novels followed. Colette and Willy became a celebrated couple in intellectual and literary circles.

|

| Keira Knightley as Colette and Dominic West as her husband Willy |

They also had a troubled marriage plagued by affairs on both sides (once with the same woman!) and eventually split. (It didn't help that in 1907 Colette discovered he'd sold the copyright to her Claudine novels for a pittance). Colette scandalized society by acting on the stage, sometimes semi-nude, and was publicly out as a bisexual. In one production, she caused a near-riot by kissing her female lover onstage.

Like the Claudine stories, much of her work was semi-autobiographical, before or after the fact. Echoing the plot of Cheri, Claudine had an affair with her stepson Bertrand de Jouvenel from her second marriage (the half-brother of her only child) when he was only sixteen, and she was in her late 40s. The scandal was one of the factors for her second divorce. But the marriage to her third husband Maurice Goudeket (16 years younger than Colette) lasted until her death at age 81.

Colette's career spanned the Belle Epoque, World War I, the 1920s, the rise of Nazism, and World War II. Weirdly, she wrote for a pro-Nazi newspaper during the War, and her last novel has some seriously anti-Semitic overtones -- though her last husband was Jewish and was actually imprisoned by the Gestapo for a few months (he was only released due to the intervention of the French wife of the German ambassador. Maurice spent the rest of the war in Paris but the couple was always in fear of a second arrest).

|

| Colette c. 1896 painted by Jacques Humbert |

However, she did lead a fascinating life. I found it so interesting how she was able to make a career for herself as a writer and celebrity for more than fifty years, especially as a woman in that time period -- she wrote about 30 novels, plus plays, essays, and countless articles and reviews. It's very impressive for a woman to have been such a prolific writer in the first half of the 20th century, especially in France where women couldn't even vote until 1944. It's a really interesting look at life at the time period. Even though I've still only read one of her novels I found it an absorbing piece of social history.

I do want to finish the Claudine novels (I have the Complete Claudine edition) and eventually Gigi and Cheri. I've also checked out the film version of Gigi from the library and hope to get to it by the end of the month. How's everyone else doing with Paris in July and the Big Book Summer Challenge?

Saturday, July 4, 2020

The Twisted Sword: The Pentultimate Poldark Novel

|

| This cover reminds me of a YA fantasy novel. |

|

| Nice cover on this edition, I think it's the Polish translation . |

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

The Fruit of the Tree: Edith Wharton Tackles Some Big Issues

Juxtaposing both the society characters she knew so well and the social commentary, it's the story of John Amherst, a young, idealistic assistant manager at a large mill in the fictional town of Hanaford, probably somewhere in New England or upstate New York. We first meet Amherst in a hospital as he checks on the condition of a worker badly injured on the job. The doctor on duty (related by marriage to the factory's manager) stoutly protests that he'll recover, but privately, a volunteer nurse reveals to Amherst that the injured man will most certainly lose a hand, if not his entire arm.

Amherst is determined to change working conditions in the factory, and his chance arises the next day -- the factory's owner, newly widowed Bessy Westmore, is here to tour the factory she now controls after her husband's death. The factory manager is home ill, so Amherst seizes his chance to tell Mrs. Westmore the truth about the factory, and his hopes to improve it. He's young, handsome, and idealistic, and Mrs. Westmore is young, beautiful, and lonely, so one thing leads to another and they wind up getting married.

|

| "He stood by her in silence, his eyes on the injured man." |

Of course, nothing is easy or happy in a Wharton novel, and a few years later, neither John nor Bessy is happy. Bessy resents the time John spends at the factory, not to mention the money the improvements are costing, and John is disappointed that Bessy doesn't seem to share his hopes to make real changes. He's getting tired of fighting Bessy's family and the people influencing her to keep him out of the mill.

Meanwhile, the young nurse, Justine Brent has also reappeared -- coincidentally she's an old school mate of Bessy's who fell on hard times and had to make a career for herself. Amherst engages her as a personal nurse/companion to Bessy, but as his relationship to his wife cools, he finds himself more and more attracted to Justine and her sense of social justice.

There are some big, dramatic plot twists, and then it turns into a bit of a sensation novel, but much wordier (imagine Wilkie Collins and Henry James writing a novel together and stole the setting from Elizabeth Gaskell). It kind of alternated between being slow and cerebral, with dramatic events. I'd get bored but then all of a sudden something super-dramatic would happen, then it would slow down again. I don't know if it's quarantine brain, but I was having a hard time with the more cerebral bits.

The setting definitely reminded me of North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell, and there are definitely plot elements that foreshadow Ethan Frome -- there's a sledding scene that is symbolic, but not nearly as pivotal as Ethan Frome. Wharton also touches on some issues which must have been very controversial for their time. I suppose this could be why it just isn't as popular as some of her other works.

I was also a bit put off by the fact that my Virago edition was 633 pages long! However, when I started reading it, I realized there was an awful lot of white space on each page, the margins are huge. I compared it to my Modern Library copy of House of Mirth which is less than 350 pages long. I checked the iBooks downloads, and they're really almost the same length. And there are hardly any editions in print. I checked the page count from the original 1907 copy and it's the same, so I suspect they're just using the same plates as the first edition. So I guess technically it counts toward the Big Book Summer Challenge.

I'm glad I read it because I am huge Wharton fan, but I don't know if I'd really recommend it. However, it's one more book crossed off my Classics Club List and one more off my owned-and-unread shelves. I still own Hudson River Bracketed but I might have to take a break from Wharton, maybe I'll tackle her biography instead.

Friday, June 26, 2020

The Complete Stories of W. Somerset Maugham, Vol. I: East and West

|

| Not the same edition as mine, but I love these Vintage International covers. |

|

| Not a particularly exciting cover, but a nice edition. |

This volume is subtitled East and West and they're drawn from Maugham's travels, many of them in the South Seas. They were written between 1919 and 1931, during the British colonial period, and many of them are set in British colonies and islands, including Malaysia, Singapore, Samoa, and Hawaii, though of course nearly all the characters are white British people. I mostly enjoyed reading the South Sea stories but nearly every one of them had some uncomfortable racist elements -- the natives are described as heathens, there are racial epithets, and most of them don't even have names (house servants are frequently just addressed as "boy." Some of the male characters have native wives and children who are just tossed aside like yesterday's newspaper. There's also some misogyny, and some anti-Semitism in the Western stories set in Europe. There's one story called "The Alien Corn" which is particularly anti-Semitic; another "The Vessel of Wrath" has some misogyny which left me aghast.